Idalis Pagan didn’t think it would be so long before she got to see her uncles. But if she can travel to the prison, like she plans to in the next month, new rules will allow her to give them each two real hugs.

Miguel and David are like older brothers to her. One is at Chippewa County prison, nearly 300 miles away from her home in Grand Rapids. The other was recently moved to another lockup.

When she was younger, Pagan said they always used to make time for her, taking her to the park, both very fun at birthdays — and the memories made trips to prisons difficult when Pagan eventually had to walk away, knowing they were staying in place.

When the pandemic hit, it had been almost a year since Pagan’s last bittersweet visit. Visitations to Michigan prisons were halted on March 13, and that one year turned into two.

“When COVID hit, there was kind of like a panic, especially knowing that some people weren't going to come out of this alive or come out of it healthy anymore,” she said.

She regretted not getting to see them before COVID happened. “You never know when things happen, or how time is gonna play out.”

It was especially hard on her mother and grandmother.

“My mom had really bad anxiety throughout this whole year. And I know some of it was because of her brothers being in prison and uncertainty and all that,” she said. “My grandma too, they were in shambles.”

Today, the Michigan Department of Corrections will resume in-person visitations with a new series of requirements and safety precautions.

“I was just really super psyched, especially knowing that they really haven't seen anyone. Like, I thought it was bad living or working from home. But no, they see no one,” Pagan said.

The new visitations guidelines require visitors to first schedule an appointment online, with a date between 72 and 96 hours of booking. Prior to entering a facility, visitors will need to take a temperature check and antigen rapid test. Masks will be provided and plexiglass will serve as a divider.

Michigan Department of Corrections spokesperson Chris Gautz said guidelines have also been amended to allow two hugs, adding that MDOC now believes visits are safe and vital for incarcerated people.

“We recognize how important in-person visitation is to our prison population,” MDOC Director Heidi Washington said in a release. “Connections with family and the community lead to greater offender success. With the continuation of vaccines and cases within the MDOC on a steady decline the department is prepared to provide in-person visits without jeopardizing the safety and wellbeing of our inmates and staff.”

But there are setbacks — as of March 25th, nineteen Michigan prisons are under full quarantine. A list of those prisons can be found here, and so, cannot be visited. MDOC warns people to monitor the list before traveling since it updates often.

Pete Letkemann is the Vice President of Citizens for Prison Reform, a criminal justice organization in Michigan. He is also part of a family advisory board that regularly works with MDOC.

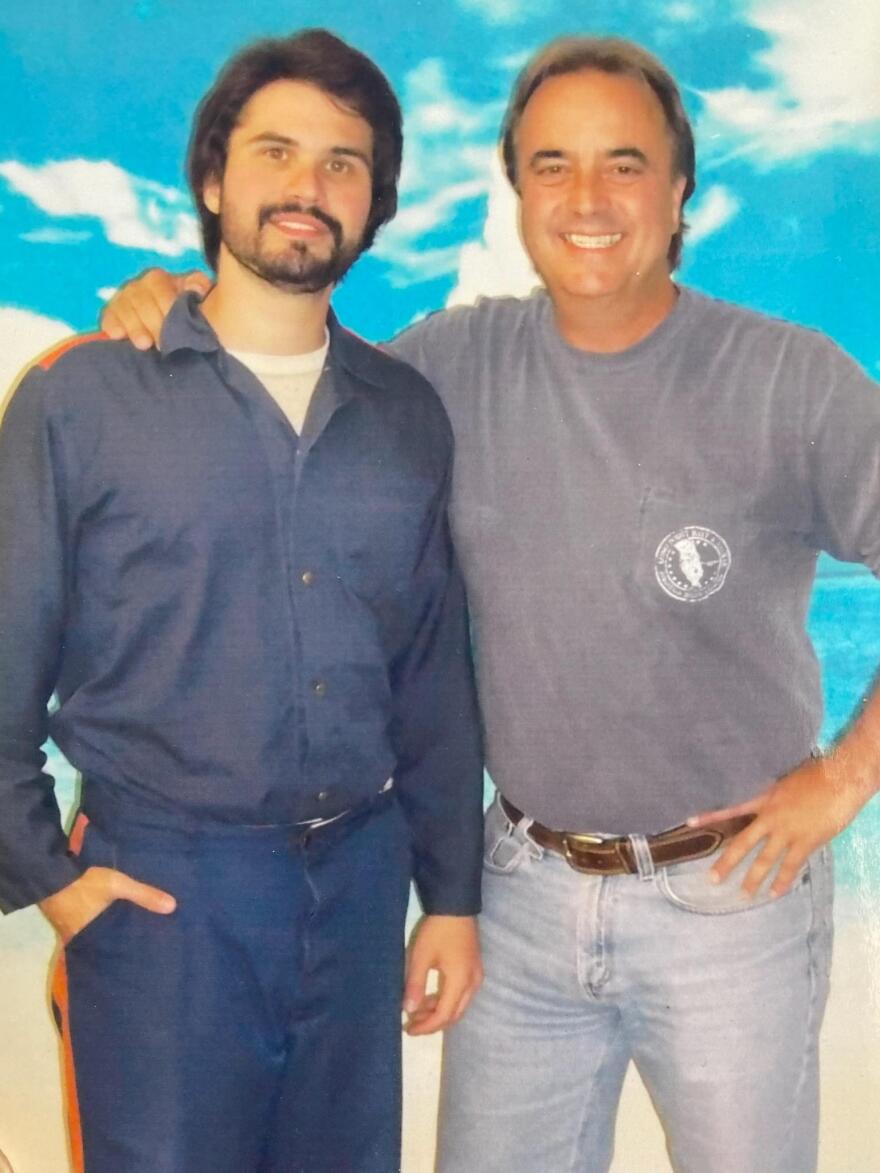

Before COVID, Letkemann would drive over four hours to Kinross Correctional Facility in the Upper Peninsula to spend time with his son, Alex. They would play cards, grab snacks and catch up for hours and hours. The walls would almost, just almost, melt away for a bit, Letkemann said.

When in-person visitations were announced this month, Letkemann jumped at the opportunity —booking an appointment for the upcoming weekend. It would be just for two hours, much less than it was before the pandemic, but he welcomed the chance to see his son’s face for the first time in a year.

“We're very, very, very close. And I know everyone says that but in this case, it's the truth,” he said with a laugh. “I would have never guessed how much of a difference it was not being able to see him and just sit there and have a conversation face to face.”

The prison, Kinross Correctional Facility, also had a flu outbreak prior to the pandemic, which also lead to visitor restrictions.

“He goes, ‘Dad, I’d give you my right pinky to get visits right now,” he recalls him saying.

But then Thursday afternoon, Letkemann found out Kinross was placed under full quarantine. The reunion was called off — just two days from seeing his son.

A visiting committee was dedicated to renewing visitations for months, Gautz said. He explained MDOC is also following guidance the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services gave to nursing homes.

“And so in nursing homes, if both the visitor and the nursing home residents are vaccinated, and they're both wearing masks, they don't have a problem with a short embrace, just like we're offering,” he said, adding they are not asking for proof of vaccination, just the rapid test.

As cases in Michigan rise, Gautz said MDOC does not have a metric outside of facilities in mind that could trigger a suspension of visiting, especially as MDOC was more confident in the rapid tests and that prisons were being vaccinated more and more.

“We're trying to look out for the mental health of the prisoners and their loved ones as well, which also affects the mental health of our staff,” he said.

But communication, before and during the pandemic, can be hard

There was a common issue even before the pandemic. Many families live far from the prisons their loved one is in and the in-person visits can sometimes be costly treks. Some people, Letkemann explained, do not have the means or time to make them. Placing incarcerated people in proximity to their support system is one thing the Family Advisory Board would like to tackle, he said.

Idalis Pagan agreed.

“If anyone out there would like to create a transportation company where they could get families to go and see their loved ones, that would be awesome,” Pagan said. “Because it's so hard, especially the farther that your loved ones are, the harder it is to see them and the more accommodations you have to make and just the planning that goes into it. It takes time.”

Phone-calls and video calls were brought up as alternatives. Michigan prisons primarily work with GTL for correctional technology.

Multiple phone-calls can be costly for some incarcerated people and they had a set amount of minutes.

Communication at the beginning of the pandemic was very difficult but progressively got better — but some facilities better than others, Letkemann said.

MDOC’s Gautz explained before suspending visits, the department director secured free calls and stamps from heads of communication companies to send electronic messages each month.

“So those calls and email messages that have largely continued. They've taken various shapes,” Gautz said.

Letkemann said these temporary free calls MDOC and GTL secured, even with some setbacks, were “a great idea.” His son’s facility also just recently got video calls installed at the end of February, but some facilities are still waiting.

“I don't fault them for that necessarily, because they get into specific facilities and they have local infrastructure issues, bandwidth, etc.,” he said. One video call with his son didn’t have audio on the family’s end.

Video calls, which are twenty minutes long, will still continue — as of March 25, twenty prisons allow for “video visitations”. Seven facilities, many of them larger with over a thousand people, are still installing them but with no date set. An MDOC release said video visitation will be available at all prison facilities soon.

Letkemann pointed out the video restrictions were almost as restrictive as in-person visitations, such as continuously staying on the screen, which could be hard on people like mothers with young children.

It also prevents people from using the restroom, showing pictures, art or seeing non-immediate family members like nieces and nephews. Letkemann’s son, for example, wouldn’t be able to see his sister’s new baby.

“(Video calls) can be such a wonderful avenue for some of these families,” he said. “I’m hoping they're going to move towards loosening those restrictions.”

In Letkemann's perspective, visitations could have been opened earlier. He said if the lockdown had been for a few months, it would be something people could get through.

“But Christmas comes and goes and birthdays come and go, and, and there was no end in sight,” he said. “I would argue that these visits are absolutely essential, keeping the family unit together and keeping people connected.”

“And I can see where (MDOC) had open things up, if that had shown to be some horrible mistake, then they'd be on the hook for it. And I get that I really do. But as the months wore on, it became more and more evident to me that this could be done safely. And now they are finally doing it,” he said.