STORY PRODUCED BY CAPITAL NEWS SERVICE

Can tiny pieces of moss become crime-busters?

Yes, according to a new study examining how law enforcement agencies, forensic teams and botanists have used moss to solve murders, track missing people, calculate how long ago someone died and – in a notorious western Michigan case, try to locate the body of a baby murdered by her father.

Fragments and shoots of moss “are easily detached or broken off and can become attached to items such as shoes, clothing or vehicles and can exist in samples of soil, dirt or other debris,” the study said. “They could be useful in establishing associations between an individual and a crime scene.”

The pieces can be as small as an eyelash.

The study advocates wider use of mosses – small, resilient non-flowering spore-producing plants in a family called bryophytes – in criminal investigations.

Mosses “can be incredibly helpful in establishing connections between unknown samples that are found and known reference samples collected at a specific location, the crime scene,” according to the study in the journal Forensic Science Research.

“The use of plant evidence in criminal investigations is an underutilized yet valuable tool in forensic science,” it said.

The authors included experts from Michigan State University, the Field Museum in Chicago, the Forest Preserves of Cook County and retired Ludington police Detective J.B. Wells.

One case highlighted in the study is the 2011 disappearance of 4-month-old Katherine “Baby Kate” Phillips near Ludington. Wells was one of the police officers investigating the case.

About a year after she disappeared, her father, Sean Phillips, wrote a letter saying his daughter had died in an accident and that he put her in a “peaceful place.”

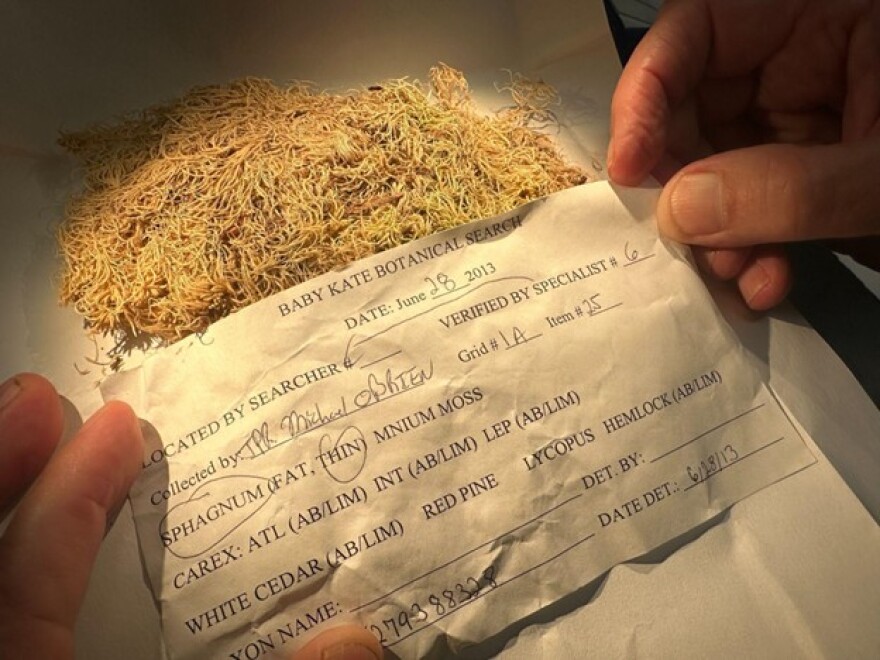

Investigators collected and identified six species of moss stuck in dried mud on his shoes.

What they found led them to Lemke Drain in a wetlands area in northwestern Mason County, a location Phillips pointed to on a map.

And although the exact location of her body still has not yet been found, it was “an area that combined the same composition of diatoms [a type of single-celled algae], mosses, sedges and trees that in all likelihood narrowed down the final resting place of Katherine Phillips from seven counties [the original search area] to 50 square feet,” the study said.

One possibility is that the baby was so young that her bones hadn’t formed long enough to survive and had fully disintegrated in the time between her death in 2011 and the site search in 2013.

Matt von Konrat heads the botanical collections at the Field Museum in Chicago and led the team of botanists and volunteers who surveyed the mosses, grass and trees in the area where Baby Kate was thought to be buried.

They were looking for a place where the dozen species found on Phillip’s shoes could be found.

Phillips is serving a sentence of 19 to 45 years at the Carson City Correctional Facility for second-degree murder. His earliest possible release date is Oct. 2, 2032, according to the Department of Corrections website.

In a Michigan case that wasn’t discussed in the new study, coauthor R. Jan Stevenson was called on to help determine whether a body found in a Metro Detroit wetland had been murdered there or elsewhere. He’s a professor emeritus of integrative biology at MSU.

Unlike in the Baby Kate case, Stevenson said he found no unique characteristics of diatoms associated with the site that would indicate if the body had been moved.

Elsewhere in the Great Lakes region, authorities in the Chicago suburb of Alsip used moss fragments in an investigation of cemetery employees suspected of digging up human remains and reselling the burial sites.

In that case, experts from the Field Museum used mosses found with disinterred remains to determine how long they had been buried. Their findings “contradicted the suspect’s timeline and placed the accused at the scene of the crime” and provided “crucial evidence that led to the successful conviction of guilty individuals,” the study said.

Moss has been used in forensic cases outside the United States as well, including to determine whether remains belonged to a person in Portugal who had been missing for six years and to determine when victims in Austria, Sweden and Italy had died.

And in a case in Taiwan, moss was used to differentiate between a suicide and a homicide, the study said.

Von Konrat, who coauthored the journal article, said, “We wanted to highlight the significance of botanical evidence because chances are investigators are simply overlooking it because they don’t know what they’re looking at.”

“We’re hoping our study helps show how important these tiny plants can be,” he said.