Ryan Klingler coached and taught Wes Leonard at Fennville High School. The town has less than 1,800 residents, so it’s rare that news from such a small town makes an impact across Michigan

However, at the end of a 2011 basketball game, the school made the headlines. Leonard collapsed, on the court, and went into cardiac arrest. He died, and it was later revealed that he had a heart condition. Following Leonard’s death, his parents, Klingler and some family friends started the Wes Leonard Heart Team in his honor.

“Our main goals were obviously to provide awareness of what sudden cardiac arrest was and how to be prepared for it,” Klingler said, “and provide automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) to schools around Michigan.”

Leonard’s death was fresh in the public’s minds with the case of Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin, who collapsed on the field and went into sudden cardiac arrest during a Jan. 2 game against the Cincinnati Bengals. Hamlin survived, in large part, due to the quick response from the teams’ athletic trainers.

Detroit Northwestern high school senior Cartier Woods died after going into cardiac arrest during a game on Jan. 31. Bystanders said immediate efforts were taken to save his life. He died a week later, after his family removed him from life support. He had remained unresponsive in intensive care.

According to Klingler, when someone suffers from sudden cardiac arrest, it is critical that bystanders know how to respond properly, as the hospital survival rate is extremely low.

“Timeliness is of extreme importance in cardiac arrest,” Klingler said. “So when someone suffers from cardiac arrest, they want to make sure they are doing CPR. It’s a huge thing. And then having an AED, those are two things that are really going to help extend somebody’s life.”

Hamlin’s injury sparked national discussion about cardiac health and how to stay prepared. Klingler has noticed this himself. The Wes Leonard Heart Team now has a waiting list of about 75 Michigan schools requesting AEDs.

“I think the awareness of wanting those AEDs around has definitely increased with Damar with his incident,” Klingler said, “and people are wanting to be more prepared.”

A large reason why Hamlin survived is because of the quick response from the Bills’ and Bengals’ training staffs. However, most athletes don’t have the same resources available to them that NFL players do. The Michigan High School Athletic Association (MHSAA), for example, has 180,000 athletes in a given year, according to Director of Communications Geoff Kimmerly.

Kimmerly had only dealt with two or three heart-related incidents in his 11 years on the job, but he said that the MHSAA has regulations in place to make sure that athletes get proper care.

“Beginning with the 2015-16 school year,we began requiring all varsity head coaches to be CPR certified, Kimmerly said. “We expanded that requirement this school year, 2022-23, to all sub-varsity teams…That’s really to hopefully guarantee that there’s someone at every practice or event that is certified in CPR and has these skills to save someone’s life.”

Kimmerly also said the MHSAA has partnered with the MI HEARTSafe initiative to help them achieve that goal. In addition to providing more AEDs to schools, the program also designates schools who are especially well-prepared for cardiac emergencies.

Waverly High School has earned that designation.Athletic Trainer Jessica Gude, who covers 2,000 students, says the coaches’ CPR training allows her to do her job more efficiently.

“If I’m at softball and there’s a soccer game going on,” Gude said, “it’s good to know that, even if I can’t get there within 30 seconds, a coach can get (CPR) started for me.”

Part of the training for an is instructing coaches how to use AEDs and making sure they have access to them when necessary.

Gude said Waverly keeps four AEDs on its high school campus, including one that she carries with her to all home sporting events and road football games.

“It’s getting care faster,” she said. “It saves me from having to say, ‘Hey, go get it’,...If I get out there right away, and I can start CPR right away, that’s going to make the difference. It could make the difference between life and death.”

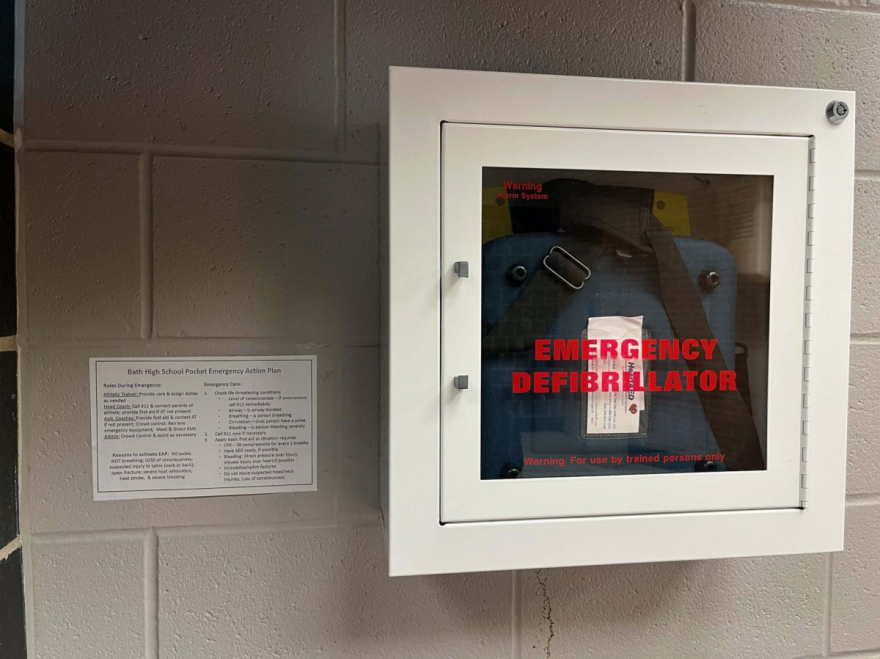

While groups like the Wes Leonard Heart Team and MI HEARTSafe are getting more AEDs in schools, there still are some without that equipment. These are often smaller schools in smaller communities, so having multiple on hand is rare. Bath High School, for example, has less than 400 students but has four AEDs on site. Athletic trainer Kelly Paquet considers this a luxury.

“I have coworkers that don’t even have one AED on some of their sites anywhere,” she said.

As important as AEDs are, schools need a plan in place to transport athletes who go into cardiac arrest to a hospital both safely and quickly. Another initiative the MHSAA had taken was having all new coaches develop an emergency action plan in the event of a cardiac emergency.

Kimmerly recalled one instance, last summer at Hastings High School ,where an action plan saved the life of a Potterville athlete who had a sudden cardiac event.

“Fortunately, there was an emergency room doctor in the stands watching his child’s team,” Kimmerly said, “but we also had people in place at Hastings that had a plan that sent people to go to the door so they could direct in the paramedics. There was a strength coach who was able to come down and begin CPR right away. There were people to go and grab the AED off the wall right outside the gym.”

Paquet works at Bath through Sparrow Health System, which has contracts with 16 high schools in the Lansing area. According to Paquet, one benefit of that affiliation is having a standardized action plan shared by each school.

“We standardized all of our emergency action plans about four or five years ago,” she said. “We’ll fill in for each other if somebody’s sick or somebody’s on vacation…So if I go cover for somebody else, we kind of have that.”

Hamlin survived because the medical staff had an action plan in place to get him the care he needed. While Hamlin had multiple doctors able to perform CPR within seconds of his collapse, high school athletes may be reliant on one athletic trainer or coach to save them until an ambulance arrives.

For Gude, seeing the response to Hamlin on TV gives her confidence that she would be able to help in a similar situation.

“We’ve gone through the schooling and gone through the training,” she said, “so watching them do it in real time, it makes the training make sense, which is helpful, because you always think ‘I have the AED, I know exactly what I would do.’ But like when you’re in that situation, it’s totally different.”

However prepared Gude, Paquet or other athletic trainers may be, nothing can tell them when a player may go into cardiac arrest. Paquet said that, for that reason, she must always be prepared for the worst case scenario.

“I go to work every day and that is a scenario that I think could happen,” she said. “Even just sudden cardiac death for some congenital thing kids don’t know that they even have, those are risks.”

That worst case scenario happened at Northwestern High School in Detroit. Woods was given CPR, for nearly 40 minutes, the school had an AED in place, and had access to a nearby hospital where he was put on life support.

Kimmerly stressed the importance of staying prepared to help with a sudden cardiac arrest since it could happen to anybody, including athletes like Woods.

“I think most people assume that it might be just the elderly grandparents in the stands watching a game or something like that,” Kimmerly said. “But it could be an official, it could be a coach, it could be an athlete, it could be anybody.”

He recalled the advice one administrator gave him.

“We might go our entire careers without ever using this AED on the wall,” he said, “but that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t have it and not know how to use it.”